![[Translate to Anglais:] [Translate to Anglais:]](https://www.invivomagazine.ch/fileadmin/_processed_/7/6/csm_320A9724-Modifier_59ec6abbed.jpg)

Recycled Bone Autograft: the Swiss Army Knife of Oncological Surgery

Publié il y a 2 mois

14.01.2026

Partager

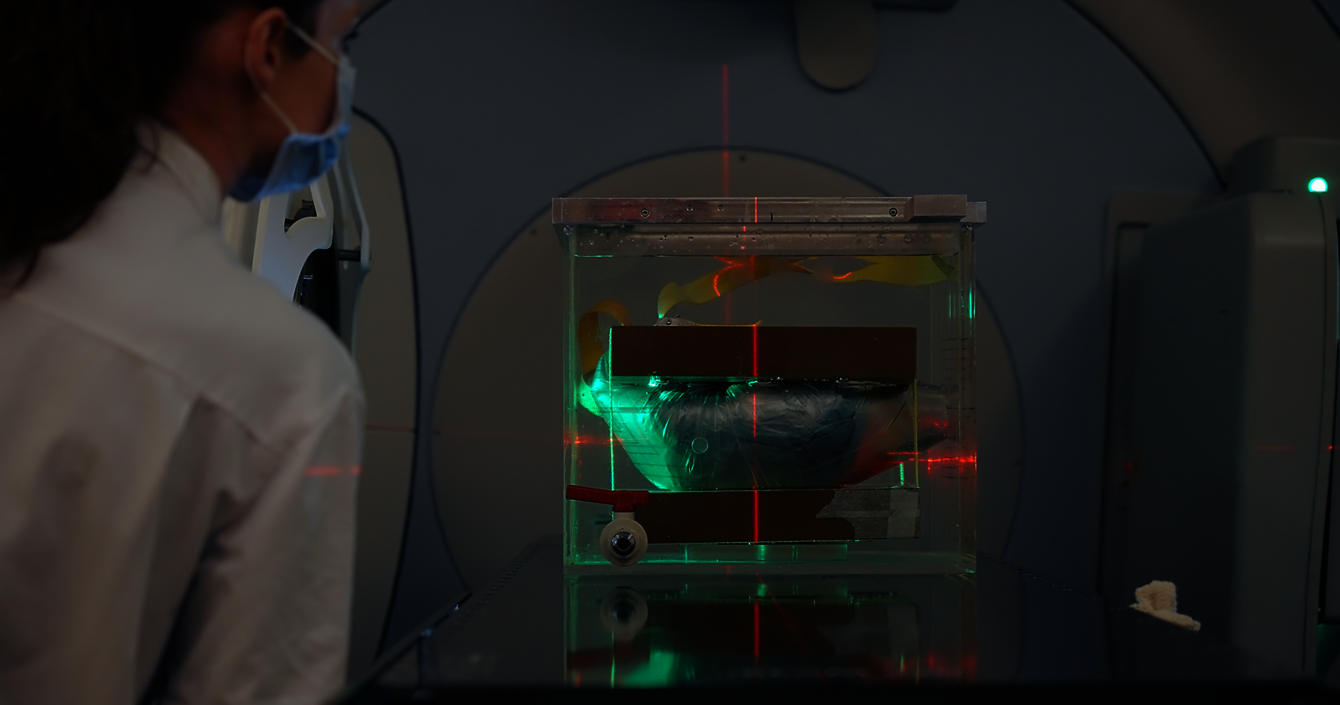

While the patient is still asleep on the operating table, their bone makes a round trip out of their body: this is extracorporeal irradiation. This technique, at the border between radiation oncology and surgery, allows the treatment of a very rare type of cancer: bone sarcomas. It consists of “recycling” the bones affected by cancer by grafting the patient’s own bone after destroying the cancer cells with irradiation. Dr Stéphane Cherix, a surgeon-oncologist at the Orthopaedics and Traumatology Service, and Dr Rémy Kinj, from the Radiation Oncology Service, have been practising this technique at CHUV since 2016. The two specialists work closely together: the surgeon performs ablation of the bone segment where the tumour is located, which is then irradiated with radiotherapy at more than 50 gray (the unit of absorbed dose of ionising radiation) before being reimplanted and reattached to the bone.

Sarcomas are rare malignant tumours, divided into two categories: soft-tissue sarcomas and bone sarcomas (accounting for only 0.2% of cancers). These are primary bone tumours, meaning they originate directly in the bone. Bone tumours are generally located in the long bones (femur, tibia, fibula, humerus), but can also affect flat bones (ribs, sternum, etc.). They are to be differentiated from secondary bone tumours, or metastases, which result from the spread of another cancer to the bone.

A dead but functional bone

Fifty gray represents a spectacular dose: “8 gray to the whole body is already a lethal dose,” explains Dr Kinj. For context, during the Chernobyl disaster, workers exposed to radiation received a maximum dose of 10 gray. After irradiation at 50 gray, the bone is as good as dead: the goal is to leave no viable cancer cells. However, "the bone’s microscopic ultrastructure remains intact," explains Dr Kinj, preserving its function.

Watch the video “Autogreffe recyclée” (Recycled autograft) by Salomé Machut.

After irradiation at 50 gray, the bone is as good as dead: the goal is to leave no viable cancer cells.

Over almost ten years, 27 patients have benefited from this approach at the CHUV. A technique that has proven its worth, according to Edona Dreshaj, who wrote his master’s thesis on the subject under the supervision of Drs. Cherix and Kinj. Of the 20 patients followed for 2 years, the overall survival rate was 94.4%. The scientist reports no cases of recurrence in the irradiated bone, which is considered reliable from an oncological standpoint. "Extracorporeal irradiation also avoids exposing healthy areas," she explains.

From amputations to recycled bone grafts

This approach is part of a long evolution in orthopaedic surgery. “In oncological orthopaedics, sarcomas used to result in amputations due to a lack of appropriate means,” recalls Dr Cherix. “Medical advances (in oncology, anaesthesia, radio-oncology, medical imaging and surgical techniques and technologies) have then made it possible to preserve the limbs.” The first documented case of bone autograft by irradiation dates back to 1947 in the United States. It has several advantages over other techniques for replacing bone affected by oncological disease, such as allografts and orthopaedic prostheses.

“The autograft is financially worthwhile: apart from the prosthetic fixation material, it costs nothing.”

Dr Stéphane Cherix

Allografting, the grafting of cadaveric bone, is an expensive technique because Switzerland no longer has a bone bank. Cadaveric bone must therefore be imported from abroad, with the risk that it may not be adapted to the patient's morphology. Prostheses vary in their functional outcomes and are also very expensive: “A pelvis prosthesis is worth between CHF 10,000 and 20,000, and a knee prosthesis between CHF 8,000 and 15,000. Recycled autograft, on the other hand, costs nothing per se, apart from the material to reattach it to the bone. It remains financially worthwhile,” explains Dr Cherix.

What does the future hold for recycled autograft?

"The future may be to bring radiation therapy equipment into the operating room," says Dr Kinj. Indeed, this technique is feasible at CHUV because of the proximity of the Radiation Oncology Service and the operating room. “In other hospitals, they don’t have intramural radiotherapy”. The two doctors plan to extend the application of this technique to more delicate areas; for example, they used it for the first time in September 2025 on the entire elbow joint, including the lower humerus, the upper radius, and the cubitus. “What makes this technique superior to others is that it can be applied to any bone in the body. It’s the Swiss army knife of oncological orthopaedics," says Dr Cherix.