AFTER DEATH, RETURNING TO THE SOIL

Publié il y a 6 mois

12.09.2025

Partager

“If I die, I want to become a tree”. This is what Gazelle Gaignaire’s mother, in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, confided in her hospital bed. To deal with this eventuality, mother and daughter faced questions that are often avoided: what happens to the body after death? And how could it be returned to the earth?

From these questions, Compost Me was born, a documentary as intimate as it is political. Filmed in Belgium, France, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and the United States, the film follows the steps of citizens, activists and funeral professionals who advocate for a radical alternative: transforming bodies into humus to nourish the earth and complete the cycle of life. Through personal accounts, Gazelle Gaignaire’s film explores natural funerary practices, in particular humusation.

“I wanted to make a living film about death”, says Gazelle Gagnaire, who has travelled through several countries to discover the new natural funeral practices.

The director gives a voice to those who think about death differently. Far from rigid rituals, these voices seek to reconnect the body to the ground and reduce the ecological footprint of end-of-life. “I wanted to make a living film about death”, she explains.

Reinventing funeral practices

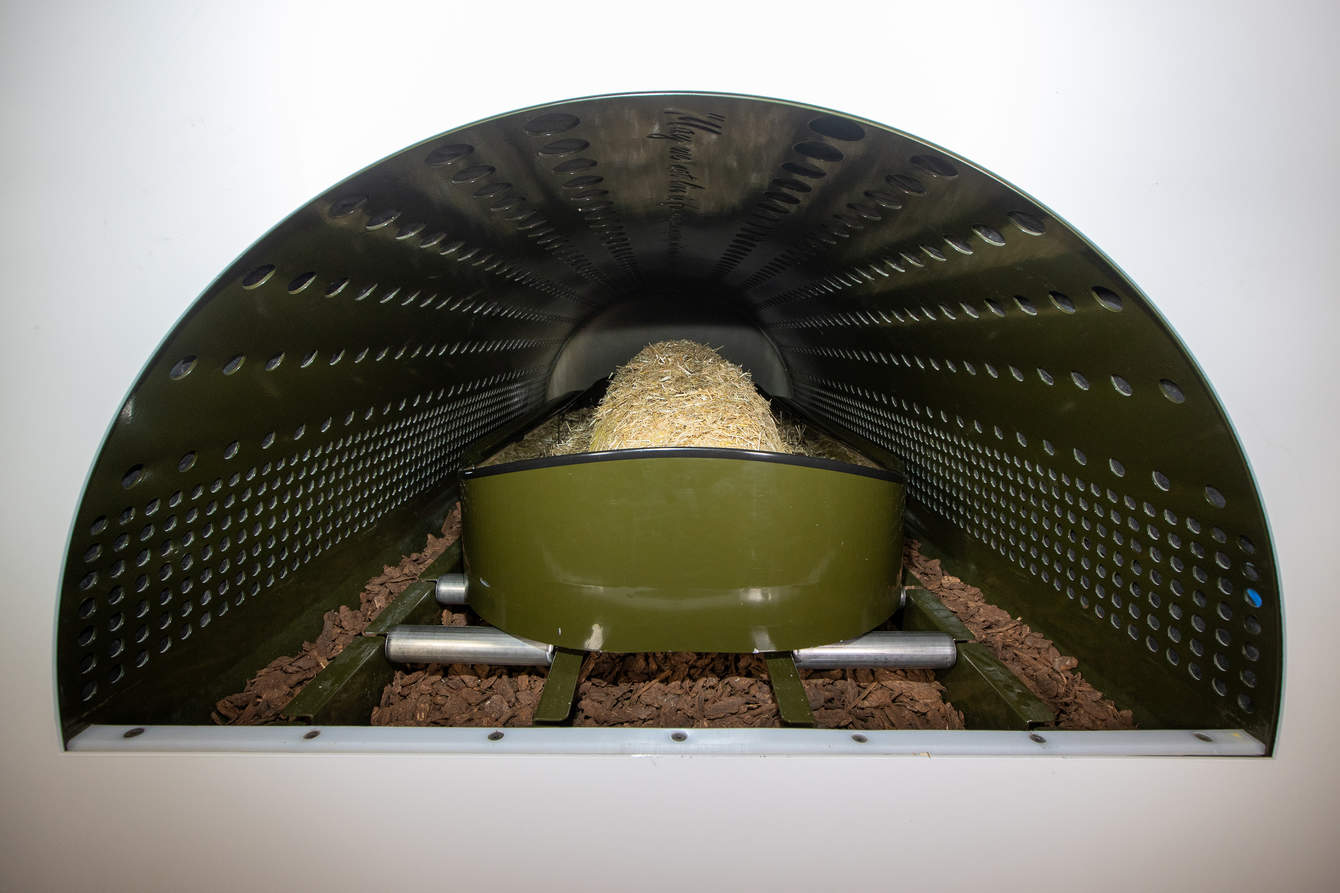

At the centre of the film is human biocomposting, a technique that transforms a body into fertile humus. In Belgium, this method is called humusation, a registered term. Governed by a rigorous protocol, it is based on the action of micro-organisms present in the upper layers of soil and allows, within twelve months, a complete transformation of the body. This takes place above ground, on a bed of crushed plants, with the body placed on it.

"Funerary practices are the ways of transforming the body, not to be confused with burials, which refer to where the remains are deposited and thus serve as places of mourning," says Vincent Varlet, professor at the University Centre of Legal Medicine (CURML). The specialist reminds us that the technical challenges of these new practices are considerable. The soil transformation process requires a strictly controlled environment, particularly regarding health, and the use of suitable plant raw materials. On the technical side, engineering must be precise: one must control airflow, temperature, humidity, and the regular rotation of the material, all parameters that must be rigorously adjusted and monitored.

Responding to the climate and existential crises

Beyond technical considerations, Compost Me proposes an almost ontological paradigm shift. For many, new funeral practices provide an answer to a contemporary spiritual quest. In a society where death remains taboo, these practices integrate the end of life into a broader cycle: that of the living.

“More and more people are expressing a need to slow down, to rediscover meaning, even in death”, explains Vincent Varlet from the University Centre of Legal Medicine. The specialist also points out that for some, the prospect of reconnecting with the earth is particularly soothing.

“It is time to ask ourselves what our body can give back to the earth”, stresses Gazelle Gaignaire. And just asking the question, in a society where death is often removed from public debate, is already a powerful act. Vincent Varlet observes a similar phenomenon: “In a hyper-connected world, more and more people express a need to slow down, to rediscover meaning, even in death. For some patients, this perspective is even soothing”, they tell themselves: “I may be carrying a cancer inside me, but the prospect of reconnecting with the earth and nature soothes me and helps me accept that it’s the end.”

An ecological and cultural fight

Environmentally, the arguments in favour of these practices exist because they are more energy-efficient than cremation, which requires temperatures above 800 degrees Celsius, and less polluting than traditional burials, often associated with the use of varnished coffins, synthetic textiles, and chemical embalming.

But before such practices become widespread, many hurdles remain, whether cultural, legal, religious or even financial. “These practices challenge our representations. For some people, this can be expressed by a loss of reference points or an attack on the dignity of the body,” acknowledges Vincent Varlet. He calls for ethical safeguards, clear regulations, and, above all, an adapted pedagogy. The specialist supervises think tanks and research groups in Switzerland that are looking at a new framework so that, in the future, new funeral practices also have their place.

There is a lot to do: train funeral professionals, supervise practices, or even avoid commercial abuses. “The goal is to invent human solutions that are ecologically and culturally acceptable”, summarises Vincent Varlet.

Planting the seeds of a new relationship to death

“By rethinking the way we treat our dead, we also transform our relationship to life,” says Gazelle Gaignaire. The body is no longer just a remains, it becomes an instrument for transmission, a return to the natural cycle, a vector of reconciliation with the living.'

Talking about death openly then becomes a societal issue, which extends to our closest relationships. “If a person can say to their parents: And you, dad, mom, what would you want after you’re gone? It’s already a huge step,' concludes the director.

TO GO EVEN FURTHER

Compost Me is a 2024 documentary on new natural funeral practices, directed by Gazelle Gaignaire.

https://imagecreation.be/film/compostez-moi/