![[Translate to Anglais:] iStock](https://www.invivomagazine.ch/fileadmin/_processed_/5/6/csm_Fille_casque_bichro_65500bdac2.jpg)

LISTENING TO THE BRAIN

Publié il y a 2 semaines

28.01.2026

Partager

[“[During my studies], I struggled to understand anything in the lecture theatre. [... ] Even when I hear noises, I can’t tell where they come from. I know it’s a person’s voice, but I can’t identify it quickly enough.” This is what Sophie, a 25-year-old Londoner, told BBC News in February 2025. Contrary to what one might expect, her hearing tests are perfectly normal. The young woman has an auditory processing disorder (APD).

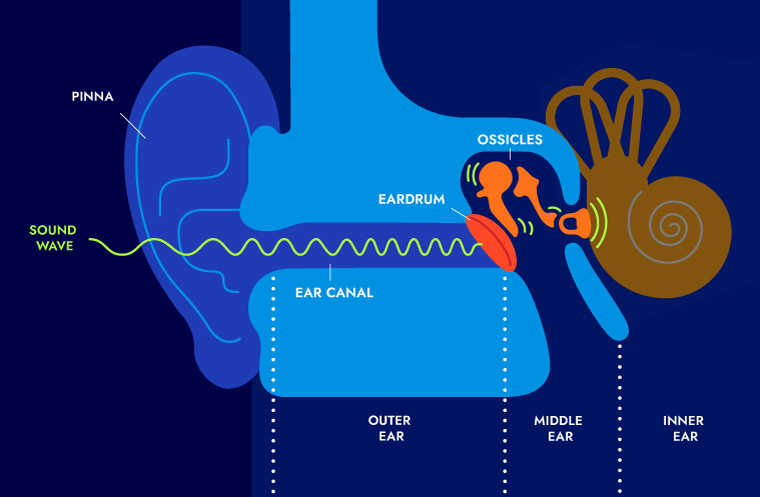

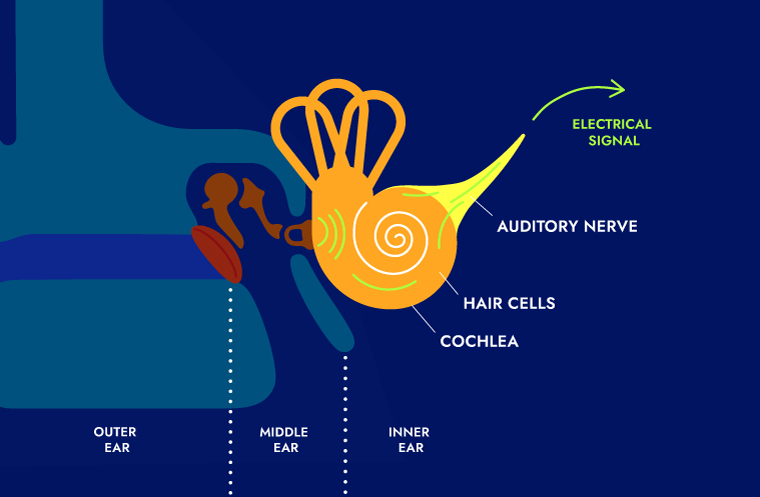

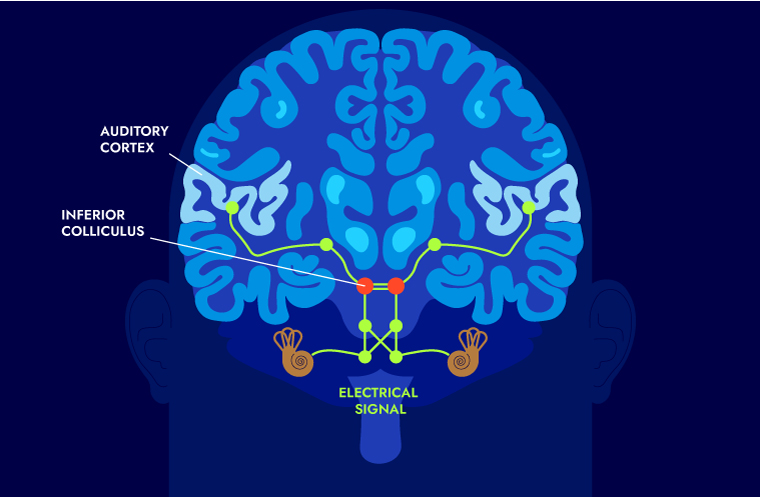

Without us realising it, the brain identifies, prioritises and continuously processes all the sounds we hear, from background noise and the hiss of a coffee machine to birdsong. These filtering mechanisms are essential for understanding what these sounds mean. But forsome people, this ability is impaired, especially in noisy environments, and specialists cannot fully explain this phenomenon. The problem cannot be linked to a so-called 'classic' hearing loss, whether it is conductive (blockage, middle ear infection, etc.) or neurosensory (due to damage to the inner ear or auditory nerve, which may appear with ageing or as a result of head trauma, for example).

Certain habits could promote the development of APD. As with Sophie, more young people showed symptoms in 2024, according to five British audiology services. Excessive use of noise-cancelling headphones and a trend among 18-24-year-olds to watch videos without sound, only with subtitles, could explain this increase. "If these behaviours last only a few hours a day, they will not have an impact," says Tania Rinaldi Barkat, a neuroscience researcher at the Brain & Sound Lab of the University of Basel. However, in the long term, these hypotheses are quite plausible: “The organisation of the adult auditory cortex depends on the sound environment in which we evolve during childhood and adolescence.”

At present, specialists still have a limited understanding of the causes of APD. “What we find is that people with APD have normal hearing on an audiogram but have difficulty understanding what they hear. One could compare the situation to a computer whose hardware works perfectly but processes data incorrectly,” summarises Lukas Anschuetz, head of the Otology and Otoneurology Unit at CHUV.

Impaired attention span

The origin of APD lies in the brain. "It is assumed that the problem originates in the central nervous system," says Anschuetz. Unlike other types of hearing loss, APD shows no abnormalities on clinical examination, conventional hearing tests, or MRI scans.

Neuroscientist Tania Rinaldi Barkat is studying how the brain processes sound, including the role of attention. “We all know there is a difference between hearing and listening. This distinction is now very clearly observed at the level of neuronal activity. Listening activates very different neurons from those involved in the simple act of hearing, notably those that allow us to focus our attention on a particular sound source.”

In the case of APD, the person may have difficulty focusing on a specific sound, which impairs their ability to interpret it. “Difficultyin locating where the sound comes from could also be involved in this disorder. Indeed, if one cannot identify where a noise comes from, it becomes harder to pay attention to it.”

Associated disorders

According to a study by the National Library of Medicine, the prevalence of APD is 5% in children and 0.9% in adults. “However, these figures may not be accurate, as diagnosing APD remains a challenge. How can we know whether a child says they do not hear a sound because they do not perceive it, or because an attention deficit prevents them from listening properly? Specialists often proceed by elimination," explains Micah Murray, Scientific and Academic Director of the research and innovation centre The Sense at CHUV-UNIL and HES-SO Valais/Wallis.

When a patient attends a hearing loss consultation, Lukas Anschuetz first performs standardised clinical audiometry, using tonal tests for hearing and word-comprehension tests for speech. “The goal is to determine what they can hear and understand. When someone hears everything but understands nothing, central investigations must be carried out with neurophysiological tests and, often, an MRI scan to exclude any structural cause. If no issue is detected, they will be referred to neuropsychology or speech and language therapy for further assessment.”

Many children with APD also have other neurodevelopmental disorders, such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), language disorders, sensory disorders, or attention disorders, with or without hyperactivity (ADHD).

When a patient attends a hearing loss consultation, Lukas Anschuetz first performs standardised clinical audiometry, using tonal tests for hearing and word-comprehension tests for speech. “The goal is to determine what they can hear and understand. When someone hears everything but understands nothing, central investigations must be carried out with neurophysiological tests and, often, an MRI scan to exclude any structural cause. If no issue is detected, they will be referred to neuropsychology or speech and language therapy for further assessment.”

It is important to distinguish between what a person hears and what they understand, explains Lukas Anschuetz, head of the Otology and Otoneurology Unit at CHUV.

Many children with APD also have other neurodevelopmental disorders, such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), language disorders, sensory disorders, or attention disorders, with or without hyperactivity (ADHD).

Treatment and preventive measures

The management of APD requires a multidisciplinary approach. "Hearing support devices can be tested to see whether patients understand better when sounds are amplified," says Anschuetz. Nevertheless, neuropsychological management is necessary to treat comorbidities.

To prevent the disorder from developing, Micah Murray advocates focused research into diagnostic methods and systematic screening of children in primary classes: “Today, children are expected to report any hearing problems themselves. Early and systematic detection would increase the chances of recovery while limiting stigmatisation. Many studies show that the earlier these disorders are treated, the greater the likelihood of equal opportunities.”