The Myth of the Pleasure Molecule

Publié il y a 1 mois

29.12.2025

Partager

It was an error of a few millimetres that changed everything. In 1954, James Olds and Peter Milner, psychology researchers at McGill University, stimulated a brain area in a rat that was thought to elicit disgust. The electrode slipped into a nearby area. To their surprise, instead of avoiding the setup, the animal returned to it and even triggered the stimulation itself, sometimes up to 30,000 times a day. The researchers saw it as a 'pleasure centre'. A foundational intuition, but a mistaken one. “Pleasure is extinguished once satiated. In this case, however, the animal never stopped”, recalls Benjamin Boutrel, a researcher at the Centre for Psychiatric Neuroscience at the CHUV.

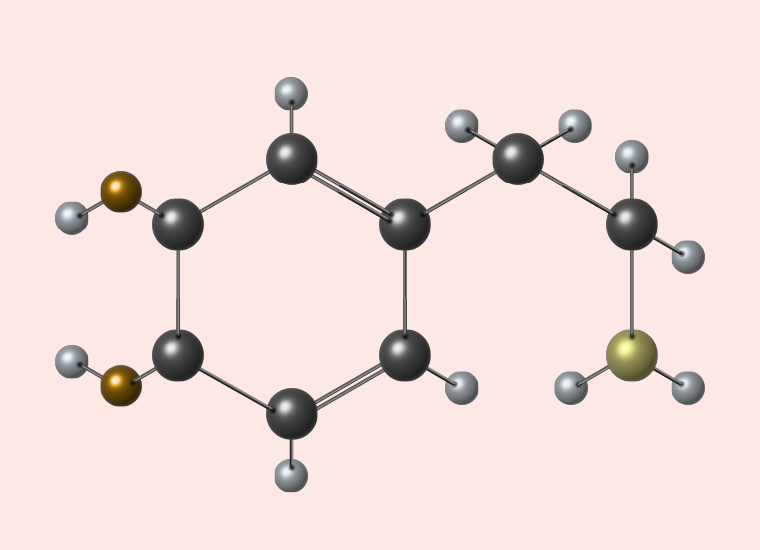

Dopamine is Mapped

At the turn of the 1960s, dopamine was identified as a neurotransmitter in its own right and mapped across different regions of the brain. We understand that it is produced from amino acids derived from food, during embryonic development, and throughout life. Its precise role remains unclear, even though its involvement in motor control had already been demonstrated through research on Parkinson’s disease.

In the 1970s, the scientific community misinterpreted the observations of neuroscientist Roy Wise: if animals appear unmotivated after blocking dopamine, then dopamine is the chemical basis of pleasure. Shortly after, it was shown that all addictive drugs cause a strong release of dopamine. This double interpretation, scientific and social, permanently created the myth of the “pleasure molecule”.

The Reward Molecule

It was not until the late 1990s that this paradigm was challenged, thanks to the work of neurophysiologist Wolfram Schultz. By observing the activity of dopaminergic neurons in monkeys, he showed that dopamine is released not at the moment of pleasure but when a reward is announced or occurs unexpectedly. It acts as an internal alert that directs attention and promotes learning. "This is the principle of reward-based learning: associating information with a reward makes it more salient and easier to remember," says Benjamin Boutrel. “In the Swiss lottery, you have a one-in-31.5-million chance of winning. Logically, no one should play. But the imagined euphoria at the moment of winning is exhilarating,” he illustrates.

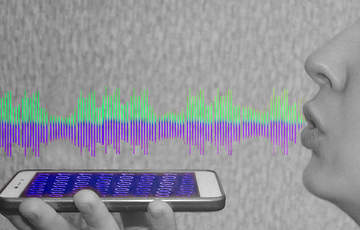

Our contemporary environment exploits this mechanism with formidable precision. “Meta, TikTok and others have picked up on the same loops observed in rats: pseudo-random rewards that keep you hooked. From lab rats to newsfeeds, the logic has remained the same,” says Benjamin Boutrel.