Publié il y a 2 mois

04.12.2025

Partager

What will hospitals look like in ten, twenty or thirty years? Above all, how will we be treated? Under pressure from all sides, the Swiss health system will face major challenges, starting with an ageing population and a nursing staff shortage. While new technologies offer promising perspectives for rethinking medical care, they also raise many ethical and practical questions.

1/ An ageing population

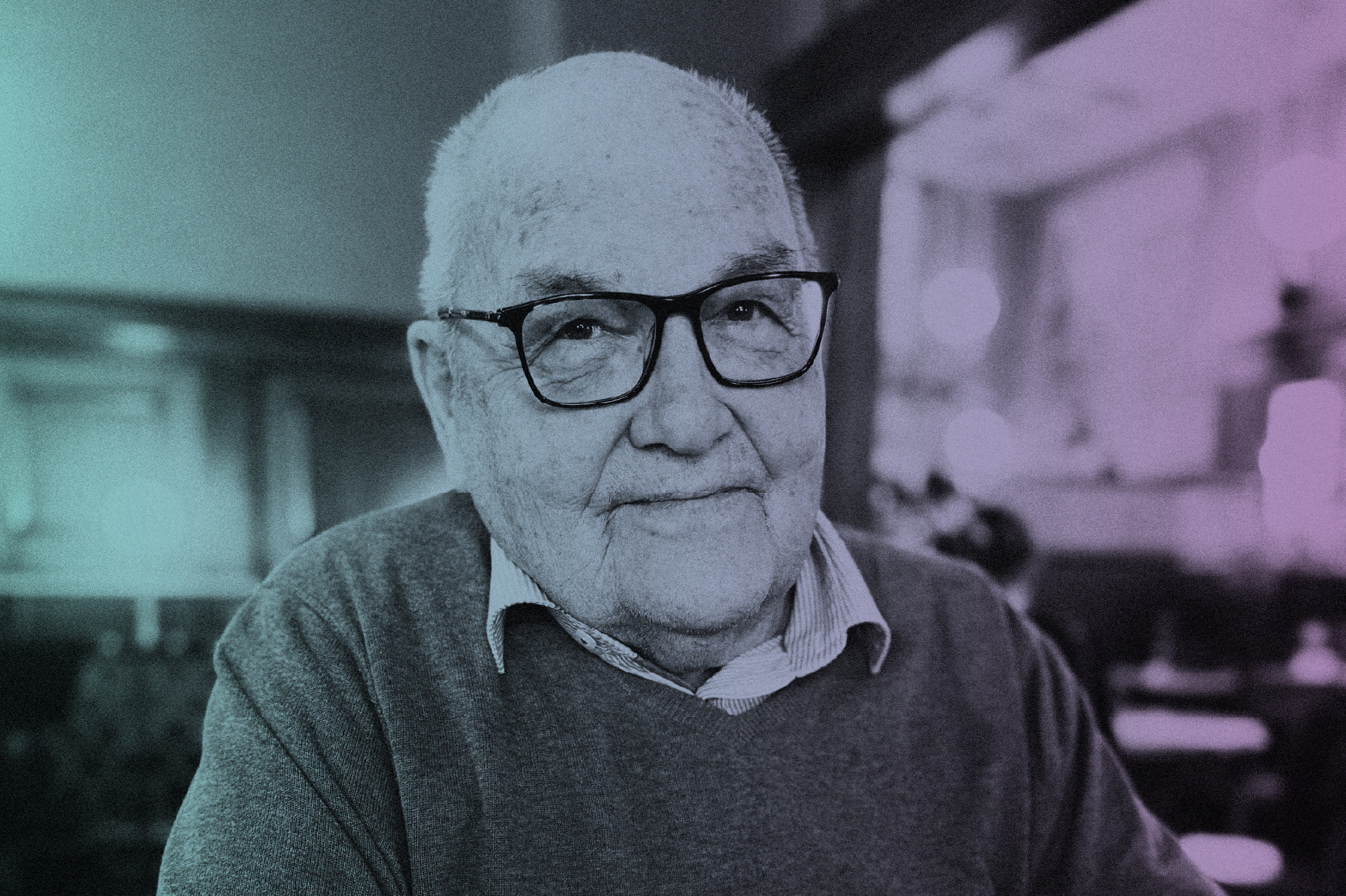

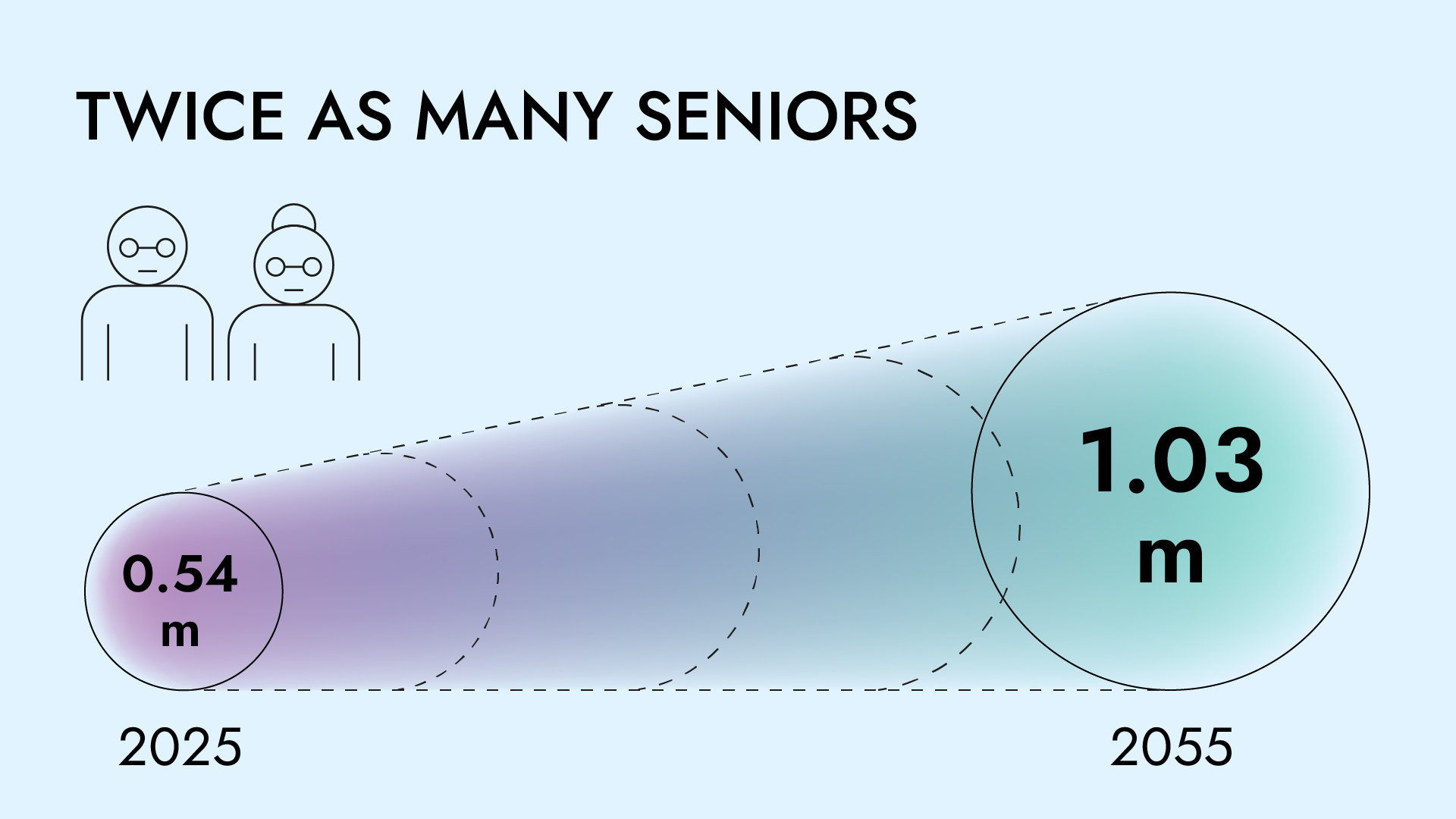

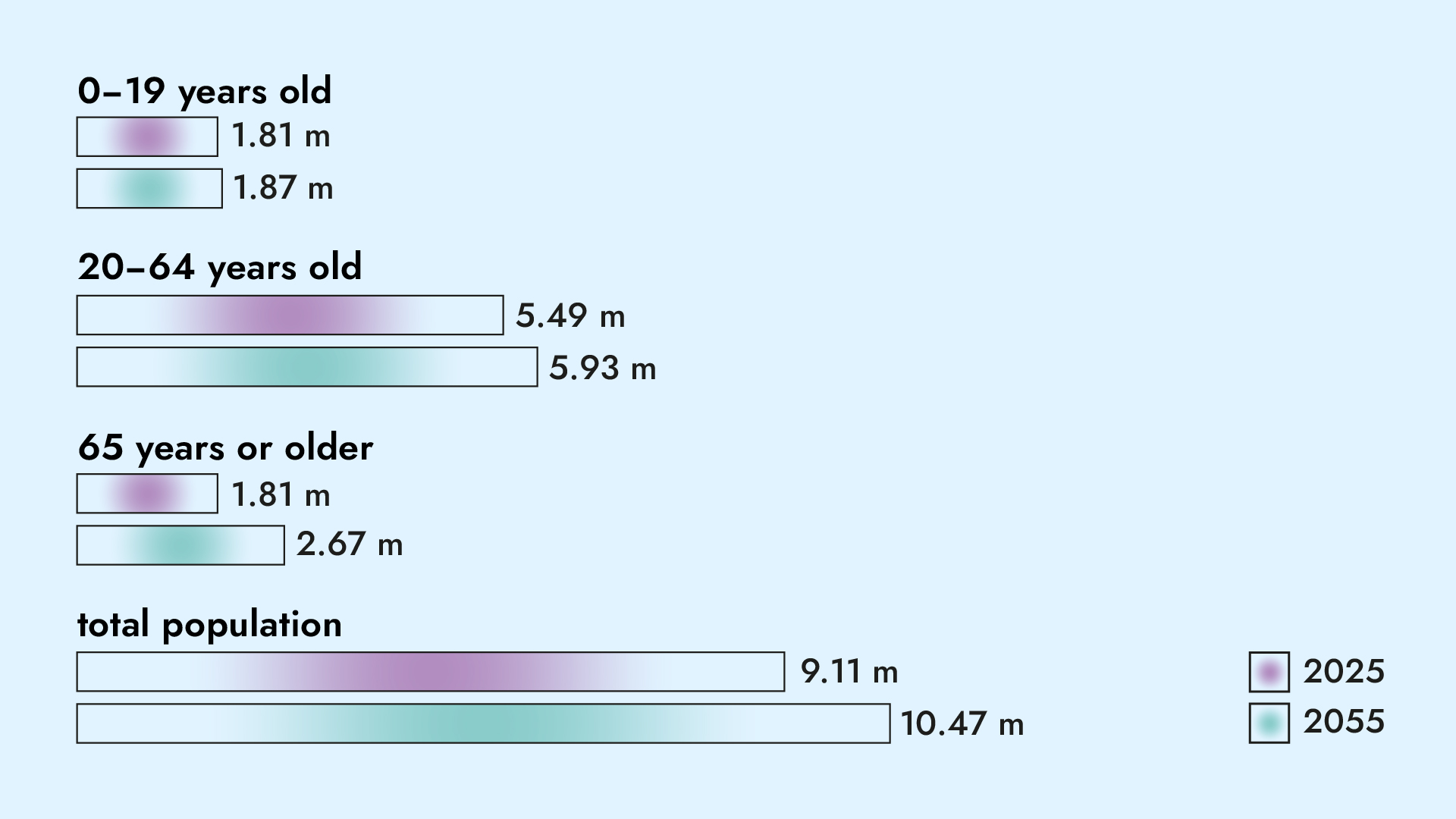

Today, Switzerland is home to about 1.8 million people aged 65 or over. By 2055, this figure will reach 2.7 million. Seniors will then represent nearly a quarter of the total population, up from 20% today. This shift complicates medical care, as chronic conditions tend to accumulate with age. "Seniors are at greater risk of complications during a hospital stay, particularly in an environment not suited to their needs," explains Joanie Pellet, assistant professor at the University Institute for Training and Research in Healthcare (IUFRS).

Initially built and organised to treat acute diseases in younger patients, hospitals are not designed to accommodate elderly patients. "Some routes through endless, poorly lit corridors without chairs to rest on resemble obstacle courses for older adults," the researcher notes.

It is a whole culture that must evolve, says Joanie Pellet, former head of the institutional programme “Hospital adapted for older adults”. “The mission is to intervene across all areas that can improve the care of older adults. Training and raising awareness among teams are part of it, but they must be accompanied by the dissemination of practices adapted to older adults, such as non-pharmacological approaches to treating acute confusional states or sleep disorders, exercises to stimulate patient mobility, or pain assessment using scales designed specifically for older adults.”

The hospital of tomorrow must prevent complications related to hospitalisation and offer a more practical framework for older adults. This includes simple measures such as better lighting, more ergonomic door handles, more contrasting-coloured stair steps, and even clearer signage at the metro exit.

To address the needs of older adults, institutions such as CHUV have established expert groups across disciplines. The programme relies on collaboration with patient partners. “We develop solutions with the people who are directly concerned. Their perspective is essential to make our practices fairer, more humane and better adapted," says Joanie Pellet.

2/ Staff is Difficult to Recruit

Patients are not the only ones getting older; teams are too. For several years, Swiss hospitals have been faced with a shortage of nurses. This situation, partly due to an insufficient number of students trained each year, has deteriorated further since the COVID epidemic, with many exhausted caregivers preferring to leave the profession. At the same time, it is increasingly difficult to recruit doctors. Some specialities, such as general practitioners, even face a real shortage (see In Vivo no 29 'Healthcare system at risk’).

FIGURE

50 years old

The average age of doctors in Switzerland.

In Switzerland, 40% of practising doctors are foreign nationals. In future, a more restrictive migration policy could pose a major threat, as Councillor Beat Jans stated on RTS. “Without the German and French staff, the Swiss health system would collapse.” For Patrick Bodenmann, Vice-Dean of the Department of Education and Diversity in the Faculty of Biology and Medicine, this pluralism is a real opportunity. “Studies have shown that staff diversity makes the population feel more welcome. It is also a key ingredient in moving towards an ideal healthcare system.”

As complex cases multiply, the staff shortage could quickly become alarming. "It is less the financial pressures than the lack of caregivers and doctors that will require a reconfiguration of the health system," says Christoph A. Meier, an expert in internal medicine and now a professor at the University of Geneva.

As a member of a global think tank on hospital transformation, he believes recruitment challenges should be addressed differently. “Do some very technical, specific interventions require a doctor’s intervention, or could they be entrusted to new, highly specialised health professions?” he asks. According to him, using workers from other sectors for certain targeted tasks would allow hospitals to recruit outside the strictly medical field. “We would also gain efficiency and perhaps even quality, because these new operators would have been trained to perform a specific single act. These people would therefore be experts in their field and able to treat a larger volume of patients than today.”

Without this reconfiguration of healthcare professions, Christoph A. Meier fears the emergence of a two-tier medical system, with private structures sufficiently staffed on the one hand and public institutions bearing the brunt of shortages on the other.

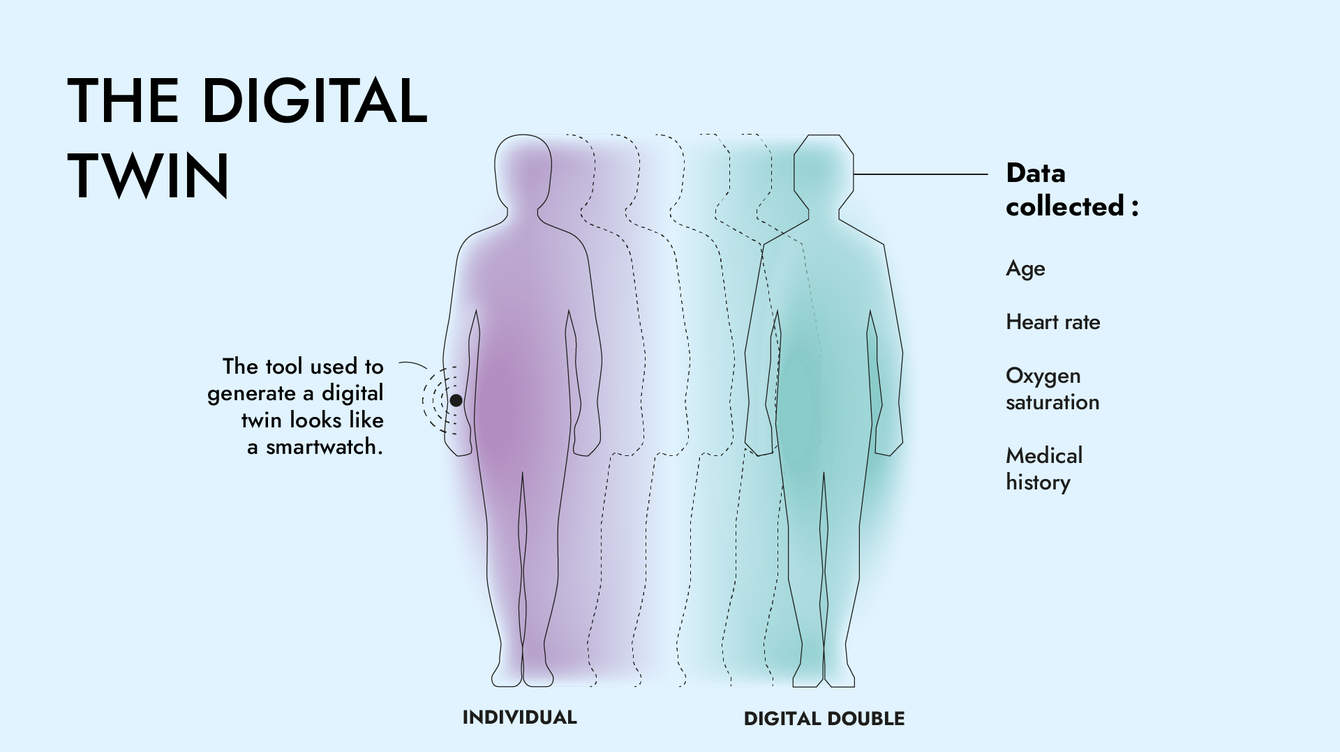

3/ New Technologies that are Disrupting Practices

New technologies offer promising prospects. "We have seen an explosion of tools over the past five years," notes Marie-Annick Le Pogam, a medical specialist in public health and prevention at Unisanté. Today, artificial intelligence can, for example, transcribe a patient's conversation, code invoices, organise hospital stays, assist in diagnosing complex pathologies, define personalised treatments, and even predict the risk of sepsis.

"Artificial intelligence can help throughout the patient’s journey," summarises Jean-Louis Raisaro, head of the "Clinical Data Science" group at the CHUV-UNIL Centre for Biomedical Data Science. Many doctors rely on it to free up caregivers' time. "Many of the tasks we perform today could be carried out by technology," says Patrick Schoettker, head of the anaesthesia department at CHUV, citing the example of measuring blood pressure.

Although their potential is immense, healthcare structures are still in their early stages. "We are starting to use AI in some applications, but no hospital in Switzerland has introduced it systematically," says Jean-Louis Raisaro. "We have increasingly sophisticated tools, but the foundations for their deployment are still lacking: quality data, compatible and interoperable digital systems, adequate training for health professionals, and clear regulatory frameworks," adds Marie-Annick Le Pogam, Program Director for the CAS programme on "Digital Health and the Impact of Digital Technology on Healthcare Systems".

Indeed, for its algorithms to work, AI must have access to a very large volume of organised, standardised data. After the failure of the electronic patient file, the Federal Council has just launched a new project. With a new name, the electronic health record will be automatically created for all citizens from 2030. It could play a central role in bringing together hospital and outpatient medical information.

Several factors explain this delay: Swiss federalism, which creates a wide diversity of information systems and standards; organisational complexity; and user reluctance among professionals and patients. "The tool is not yet very user-friendly and has not really proven itself, which explains its limited adoption," analyses Marie-Annick Le Pogam.

Another challenge inherent in new AI tools is certification. To establish a diagnosis, the collected data must be highly reliable. However, this is not yet the case. “These processes take a lot of time,” notes Patrick Schoettker.

“We are being heard, and we can see improvements”

“I am on my 630th day of hospitalisation,” announces Eric Pilet, immediately and soberly describing the various pathologies that affect him. This valiant octogenarian knows his way around the CHUV, an expertise he uses in the mission entrusted to him. For several years, the retiree has participated in the Hospital Adapted for Older Adults (HAdAs) programme as a patient partner. He is regularly consulted as a senior expert on the hospital environment.

Eric Pilet remembers the programme's launch perfectly, shortly before the pandemic. “The CHUV management found that most of its patients were over 65 and considered it necessary to adapt the hospital accordingly.” Accompanied by two other patient partners, the Lausanne resident says he initially struggled to find his place. But the collaboration has rapidly evolved. “This programme is starting to bear fruit. We are being heard, and we can see improvements.”

During working sessions, this former painter and construction company boss conveyed several messages. He cites the example of shiny floors or walls of the same colour, which can bother visually impaired people. The seniors also stressed the importance of modular lighting in rooms and corridors, chairs with armrests, and adapted stair ramps. “Some of these recommendations are not only relevant to seniors.”

This autumn, Eric Pilet attended the site meetings on the renovation of the rooms on the 16th and 17th floors of the CHUV, with a small victory to show for it. “I had realised a long time ago that there was no electrical outlet near the nightstands. After many discussions, the installation principle was accepted.”

Eric Pilet uses his hospital stays to explore certain issues in depth. During each visit, he scrutinises the latest innovations with his keen eye, analyses his care pathway, then takes out his large brown notebook to record his observations. Lately, the expert-patient was admitted to acute geriatrics, "a closed unit," he stresses. A hospital area from which one cannot go out freely. “I didn’t understand why I was there, among patients with cognitive disorders, sometimes severe. That’s when I understood how crucial it was to explain to patients who are fully in possession of their intellectual capacities why they are in a closed unit, and especially to confirm to them that their lucidity is recognised.”

By nature enthusiastic, Eric Pilet takes great pleasure in his role as a senior patient partner. He recently made several videos to raise awareness among CHUV staff of good and bad practices in healthcare, reception, medication, and even sleep. “It nourishes me, keeps me busy, and fascinates me. Since 2008, I have received a lot from the hospital, so I also wanted to give back.”

4/ Reducing the Carbon Footprint

"The healthcare system alone accounts for 6 to 7% of greenhouse gas emissions in Switzerland, a large share of which comes from hospitals," says Nicolas Senn, vice-dean for sustainability at the Faculty of Biology and Medicine at the University of Lausanne. "If we want to comply with the Paris Agreement, a commitment formally made by Switzerland, we must divide our emissions by 10.”

Hospital structures can act on several levels: improving building insulation, promoting soft mobility among employees and patients, or even reducing the proportion of meat products in meals. Measures are also being taken in the medical field. Certain environmentally harmful drugs have been replaced. This is the case with desflurane, a ‘convenient’ anaesthetic gas with a catastrophic climate footprint. Since 2020, the CHUV has banned its use, preferring injectable anaesthetics, which are far less polluting (see In Vivo no. 28 'Medicine and sustainability: the challenge of the century').

Reflections are also underway to reduce the use of single-use equipment. "We have gone too far in this respect; it is no longer justifiable today," says Nicolas Senn. Some actions can be implemented directly by hospitals; others require a profound transformation of the health system. “We need to reassess the hospital’s place in the global care network,” says the scientist. “Does this patient necessarily have to be treated at the hospital? A urinary infection treated in an emergency room requires much more time and energy, due to the extensive procedures required by hospital structures, than if it were treated by a general practitioner.”

According to several studies, reducing the carbon footprint of health systems requires developing community care. These services are delivered outside hospitals, particularly in prevention and health promotion. Changes in practice will also be needed to avoid unnecessary medical procedures. “MRI scans are among the most energy-consuming exams. However, we know that 30 to 40% of those that are carried out are not clinically useful,” the specialist reports. For sociologist Claudine Burton-Jeangros, the health system is marked by strong tensions between individual interests and collective concerns: "Everyone takes exception to the increase in premiums, but when we try to streamline, people get prickly," observes the professor at the University of Geneva. According to her, in the face of environmental constraints and an ageing population, healthcare structures will have to prioritise certain actions at the expense of others.

5/ The Hospital at Home: The Solution?

Faced with these multiple challenges, many specialists believe the hospital of the future will be a point-of-care facility reserved for acute cases. “Stays will be limited to the minimum time, with treatments continuing and ending at home,” says Friederike J.S. Thilo. This, in particular, is made possible by new digital tools enabling remote monitoring and by medical teams moving directly to patients’ homes, explains the professor specialised in digital health and nursing at the Bern University of Applied Sciences.

This paradigm shift could have many advantages. “Patients recover better at home”, stress several doctors. “There is no risk of hospital-related infection and much less delirium or disorientation.” On the economic front, reducing the number and duration of hospital stays would also allow institutions to achieve substantial savings.

For this to work, effective collaboration among all health stakeholders is essential. “The hospital of the future must be part of an integrated network,” says Meier. “Promoting synergies is by far the most difficult task and much more complex than buying a new robot. For this, the university hospitals must set an example and serve as models in the transformation towards greater collaboration.”

![[Translate to Anglais:] ©Large Network](https://www.invivomagazine.ch/fileadmin/documents/images/FOCUS_futur/LN_INVIVO_HOPITAL-FUTUR_MINIATURE_MINIATURE.jpg)

![[Translate to Anglais:] ©Large Network](https://www.invivomagazine.ch/fileadmin/_processed_/6/8/csm_LN_INVIVO_HOPITAL-FUTUR_MINIATURE_MINIATURE_337551332d.jpg)