Publié il y a 4 mois

23.07.2025

Partager

To live with HIV and lead a similar life to the rest of the population? In Switzerland, not only is it possible, it’s the norm. Today, anyone who carries the virus and is on effective antiretroviral treatment will not develop AIDS. (S)he will not transmit the virus either. A reality often overlooked. In question, the weight of popular belief, usually discriminatory, and a poorly informed population.

Since the beginning of the epidemic, progress in treating and understanding HIV has been considerable. Matthias Cavassini, head of the infectious diseases department at CHUV, sums up the situation: “The answer to the question ‘what has changed in forty years?’ is simple: everything has changed.”

The turning point of 1996

The Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) is a retrovirus that attacks the immune system. Without treatment, this infection can develop into acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, known by its acronym 'AIDS'. It was in 1981 that the first cases of AIDS were reported in the United States. This global epidemic causes HIV infections, which, in the absence of effective treatments, evolve into AIDS. For a long time, the virus has remained mysterious and formidable. It generated a real social panic, which resulted in the stigmatization of the most affected populations, like the gay community.

For years, HIV-positive people have lived with a highly reduced life expectancy. They do not die of AIDS, but of other infections and cancers that take advantage of their immune system, which HIV highly weakens. It would take fifteen years for an effective treatment to emerge. The year 1996 saw the arrival of triple therapies. For the first time, a combination of drugs effectively controlled the virus, reduced its viral load, and restored immunity to patients. HIV became a chronic disease that was no longer necessarily fatal.

Lexique

Person on effective treatment

an individual living with HIV but not transmitting the virus.

High prevalence population

groups of people in which HIV is statistically more present.

Undetectable viral load

the virus is present but not transmissible.

Triple therapies and spaced injections

Over the years, treatments have constantly improved. They have become easier to follow, better tolerated, and less restrictive. “When the first HIV treatments appeared, they were invasive and burdensome for the patients. This is no longer the case. The quality of life is greatly improved,” explains Matthias Cavassini.

Today, long-acting injectable treatments are available. These subcutaneous treatments allow for two intramuscular injections twice a month. “In the future, we hope to be able to treat with bi-annual injections.” Now, the life expectancy of HIV-positive people is comparable to that of the general population. As a result, the daily life of a person living with HIV is almost no different from that of the general population, except that lifelong treatment remains necessary.

What about healing? “The situation is complex,” says Cavassini. To date, only a few cases of remissions have been documented, often following bone marrow transplants performed to treat hematological cancers and not HIV directly. “This suggests new avenues of research, but they are not accessible for patients yet”, stresses Matthias Cavassini. For the specialist in infectiology, the current priority is universal access to antiretroviral treatments, which make it possible to live with HIV without transmission or disease progression. In many countries of the African continent, this access is currently threatened by political decisions, including those of US President Donald Trump. "We must realize that the situation is urgent: we must continue to reduce the number of new infections and fight against such decisions which risk wiping away years of the fight against HIV," insists Matthias Cavassini.

“When I received the diagnosis, I thought I would die within a year.”

“A tsunami of emotions”, she describes. Despite her medical knowledge, she is immediately thrown back several years. “I did my training in London. My first position was in an emergency unit where we welcomed AIDS patients with emaciated cheeks, with Kaposi’s sarcoma, a form of cancer that causes spots on the skin or opportunistic diseases... When I received the diagnosis, I thought I would die within a year.”

Very quickly, the medical teams reassured her. She knew the right questions to ask. She understood that she was not going to die, that she was going to live. And even live well. Yet, another fight began: that of silence. “At the beginning, I didn’t want to talk about it. First, I had to accept the illness. I was one of the people who thought they were informed, when in fact I wasn’t. Even in some medical fields, the advances in HIV are not well known. I stigmatized myself.”

During the first three years, she kept everything to herself. “The secret, the fear, it’s a huge weight. I have met people who have been living with HIV for years without ever speaking to anyone about it. To their friends, to their families.”

She also lived in this paradox: “I knew that I was not contagious, that I could live a normal life, have relationships, children, breastfeed. But I didn’t dare to talk about it. It must be said that around me, no one was talking about it. At one point, I told myself that it needed to change and that I was a hypocrite. How can I expect others to talk about their HIV-positive status if I hide mine?”

Today, she is 57 years old and feels in great shape. Above all, she decided to talk, precisely so that things could change. “HIV is not a divine punishment, nor a question of sin. This religious or moral discourse, this internalised guilt, it’s destructive. We must talk about it, without stigmatising. It’s a chronic infection, but we are not sick. Until we talk about what it’s like to live with HIV today, people won’t get tested. And they will continue to put themselves in danger.”

Even if some fears resurface – like during the Covid pandemic, where every fever reminded her of how vulnerable she was – Ellen is now living with serenity. “Around me, no one has rejected me. I live much better, psychologically and emotionally, since I talked about my diagnosis. There should be no need for projects to speak out. But as long as it is necessary, I want to carry on and participate in these projects. I want to say: we are here, we live well, and we have nothing to be ashamed of.”

Transmission: a transformed reality

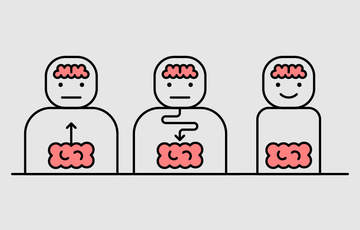

Among the major advances in research, one of the most shocking concerns the transmission of the virus. A person living with HIV and on antiretroviral treatment becomes non-transmissible once their viral load remains undetectable for six months. This principle, known as “Undetectable = untransmissible,” is the result of a medical revolution that allows serodiscordant couples—one partner carrying the virus, the other not — to live peacefully, without risk of transmission even during unprotected sexual intercourse.

For Matthias Cavassini, another situation shows how far medical research has come: that of pregnant women. “Without treatment, the risk of mother-to-child HIV transmission during vaginal birth is 25 to 30%, which is enormous. But today, a woman who starts a tritherapy during pregnancy can give birth vaginally without risk to her baby.” This breakthrough opens the way to peaceful motherhood for people living with HIV. "They can even breastfeed without danger for the child." Switzerland is considered a pioneer in the monitoring of pregnant and HIV-positive women. Since 2018, the Swiss health authorities have been supporting mothers who wish to breastfeed and whose viral load has been undetectable for six months.

Persistent and false stereotypes

Among respondents to Gilead Sciences’ survey 'How well informed are we about HIV in Switzerland, 2024':

78% are unaware that an individual living with HIV, and on treatment for at least 6 months, cannot transmit the virus through sexual relations.

45% got tested.

22% think that a kiss transmits HIV.

7% think that HIV is transmitted by sharing a toilet.

Source: Gilead Sciences Survey :«Dans quelle mesure sommes-nous informé-e-x-s sur le VIH en Suisse, 2024»

A social reality out of step

Scientific progress has revolutionised the management of HIV. But society struggles to keep up. "There is a profound gap between the fantasized image of HIV and the medical reality," observes David Jackson Perry, PhD in sociology and coordinator of projects related to HIV at CHUV.

The confusion between HIV and AIDS is one example of a society lagging in its perception of the virus. In media discourse as well as in everyday language, the two terms are often used interchangeably. “It is not uncommon to hear someone say 'have AIDS' to refer to a person living with HIV. Now, if this person is on treatment and it’s effective, they will never develop AIDS and never transmit the virus. It is a confusion that is not only false, but also discriminatory,” the specialist insists.

This semantic shift fuels a negative vision of HIV, disconnected from contemporary realities. And this is only the visible part of a more global knowledge deficit among the population. “What is worrying is that almost 80% of people think they are well informed, while a large part of them do not exactly know how the virus is transmitted.”

In fact, this ignorance is not limited to the general public. “Studies show that even some health care professionals do not fully control the modes of transmission or the effectiveness of treatments. This can lead to errors in management, or even denial of care,” warns the sexual health specialist.

For him, society must reconsider its relationship with HIV and its knowledge in this area. And this involves a more open and inclusive discourse around sexuality. “We must stop thinking that only certain communities are concerned. Everyone is concerned, including heterosexual people,” he says. The data confirms it: in the UK, for example, new transmissions among heterosexual people have recently surpassed those seen within LGBTQIA+ communities.

This paradox highlights a major challenge in prevention. “The message is difficult to convey: we should not scare people, but we must hold them accountable. It’s a difficult balance. People must be sufficiently aware of what HIV is – a chronic disease that can affect everyone – so that they feel concerned and get tested. This is the urgent matter: to make screening routine.”

HIV: name properly to better understand

Too often, HIV is still referred to with outdated, stigmatising, or medically inaccurate terminology. Yet, the right words exist—semantic overview.

Who are the people concerned?

We no longer speak of “AIDS patients” or “seropositive”, but of people living with HIV. This expression reflects the current reality: with effective treatment, one can live a long, healthy life without transmitting the virus. The term "risk groups" should be replaced by "unsafe practices". As HIV is strongly associated with the gay community, many heterosexual people, especially men, do not feel concerned, while infections are increasing among this population.

How to talk about it?

We avoid talking about “infection” or “HIV cases”. Instead, we will say: new diagnosis or newly diagnosed person. HIV is not a judgment, let alone a punishment: it is a medical reality that must be managed.

What about transmission?

No more guilt-inducing terms like “unprotected sex”. We talk about sexual or vertical transmission (from mother to child), integrating the concepts of risk reduction.

Unlearning fear

If HIV continues to inspire so much fear, it is also because of its imprint in the collective imagination. The prevention campaigns of the 1980s and 1990s, often alarmist, have made a lasting impression.

In Switzerland, the comic book "Jo" by Derib, massively distributed in schools, is an example. We follow a teenager infected with HIV, whose condition rapidly deteriorates until death. The emaciated faces, the omnipresent pain, and the tragic end have left an indelible mark on the collective subconscious.

This work, like so many others at the time, deeply associated HIV with suffering, shame, and a fatal outcome. However, this image in no way corresponds to the medical reality in 2025. "It is time to deconstruct these representations inherited from the past to make way for accurate, benevolent, and updated information," concludes David Jackson-Perry.

“At the time of diagnosis, we have to update patients' knowledge”

Isabel Cobos and Corine Courvoisier are clinical nurse specialists. Both work for the outpatient infectious diseases consultation at CHUV. Alongside other health professionals, including David Jackson-Perry, they have set up discussion groups where people affected by HIV meet and exchange.

On the ground, the two women are on the front line helping patients to accommodate a recent HIV diagnosis. “We often meet with patients shortly after their diagnosis has been announced. What we notice is that many refer to very old representations, influenced by images of AIDS seen in films or heard in stories dating from the beginning of the epidemic.”

This discrepancy between the current reality—an HIV that has become a chronic disease — and collective imaginations is a major issue. “It is essential to reassure, update knowledge, and show that one can live with a good quality of life.”

Because living with HIV is mainly about deconstructing preconceived ideas about the virus. “We explain to the person that they will be able to live normally, have relationships, children... But it is still necessary that (s)he manage to integrate these elements. It is this path that takes time," explains Isabel Cobos.

“Many of our patients don’t know anyone else living with HIV. This reinforces the feeling of being alone,” adds Corinne Courvoisier. To respond to it, the two caregivers have set up collective workshops around sensitive issues, such as emotional and sexual life, the announcement of the diagnosis, or even aging. "The idea is to promote the sharing of experiences, to encourage people to regain control over their health," insist the caregivers.

A mentorship program also completes this plan. It allows people living with HIV, from various backgrounds, to make themselves available to support other patients. “This lived experience has a reach that our professional messages do not always have. It creates connection, identification, and even a real trigger," explains Corinne Courvoisier.

![[Translate to Anglais:] IMAGE : iStock](https://www.invivomagazine.ch/fileadmin/_processed_/5/d/csm_LN_INVIVO_Solitude_MINIATURE_65232ce669.jpg)